Well here we are, folks, the final list of my top movies of 2010. As I said in last week’s post, I’ve seen a hell of a lot of movies this year, and plenty of them were pretty good. For all the disappointment I felt this summer brought, come fall it seemed one great thing was coming out after another. As overwhelmed as I kind of felt during the worst of it, it seems to have shaken out more or less, and I feel comfortable with the number of things I’ve seen this year.

If you feel like checking my work, you can feel free to look through my list of movies I saw in 2010, but I don’t really think there’s any noticeable absences that would have made their way onto this list. I already spilled well past the borders of ten movies anyway, with many that I had fully intended to write about hitting the cutting room floor once I got serious about trimming the list down. As it is, I don’t think I could cut any of these picks without feeling as if I’ve betrayed my experience of this year. I love all of these movies fully.

The movies aren’t sorted in any particular order, and I have no intention of claiming one is better than the other. I found a surprising correlation between my picks and most of the major critics of note this year, which makes me think I need to either A) see weirder stuff or B) start charging to talk about these movies. Hell, if my list can so closely mirror people who do this for a living, why am I doing it for free?

Of course, all of that aside, great movies are great movies, no matter who calls them so. These are some great movies. I hope you find the list worth your time. If something sounds interesting, go out and watch it! None of these movies are secret traps of so-bad-its-good. And feel free to share your list in the comments, or tell me how wrong I am, or maybe even agree with me. I mean, that last one isn’t as interesting, but I don’t mind being right.

All right. No more preamble! Here comes

My Top Not-10 Movies of 2010

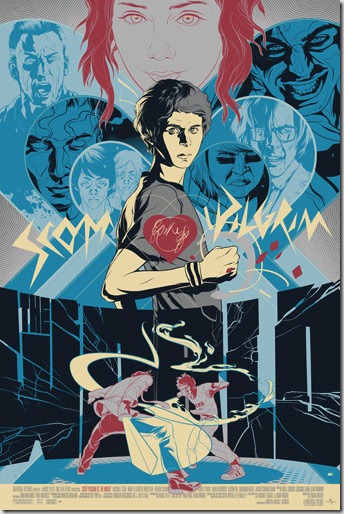

Scott Pilgrim vs The World

directed by Edgar Wright

But what Scott Pilgrim really is is a love letter to visual storytelling. It’s a movie that lives to mesh images with words and dialogue and sounds to create something new and exciting. In adapting the original graphic novel Edgar Wright has gone far beyond the most abstracted examples (Ang Lee’s version of Hulk, Sin City) to mesh conceits of that storytelling style into a filmic space. Sound effects aren’t just given special notice, but they permeate the film. Scenes slide into frame like panels, with aggressive use of split screen and jump cuts to create the feeling of the original graphic novel without relying on the actual animation of said panels to overstate the point. Speed and sound lines drip off of everything. It’s lush with effects, creating a world that’s part cartoon and part comic book but still feeling complete and grounded in its own strange reality.

Scott Pilgrim is an ambitious film, in parts incredible action film, broad coming-of-age comedy, and off-beat romance. But what its eccentric cast represents is the broken individuals of my generation, people too self-aware to not realize that they’re a mess of cliché but unable to do anything about it but laugh at themselves. Nobody is wholly good, and the heroes are often as petty as the villains, but when isn’t that the case? For all its unreality, Scott Pilgrim presents a more colorful version of the life I think most people live out every day.

Of all the movies on this list, I feel Scott Pilgrim is the most fun, the most creative, and potentially the most flawed. But it is amazing for all the things it reaches for, even if it doesn’t quite capture them. It’s a film full of magic, insightful and clever even when it’s being stupid and awkward. For all its unrealities, it is about the truth of all of our dreams, the life we live within our imagination.

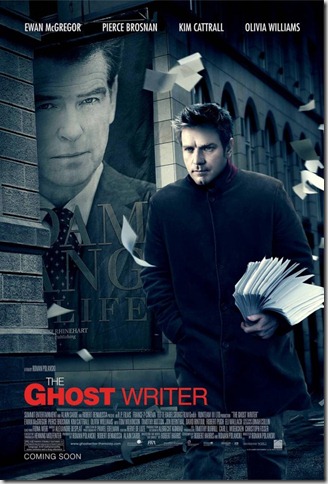

The Ghost Writer

directed by Roman Polanski

The best thing about The Ghost Writer is how muted it is as a thriller. It’s laid out from the outset that whatever secrets are here have caused the likely death of one person already, but at the same time the story is about an author doing research for a biography. The ticking clock so paramount to the genre is almost non-existent, with only the hazy idea of a deadline for the book keeping McGregor’s writer moving at times when he’d happily rather just not push deeper into the labyrinth of the plot.

And it’s that easy pace that really makes The Ghost Writer surprising. Things unfold almost casually but end up in dark places, with conspiracies and paranoia blossoming naturally in the environment of political intrigue we find ourselves. It’s obvious that nobody is entirely trustworthy but it’s not clear whether it’s because of some dark secret or because that is simply the reality of modern politics.

Special note should be given to Brosnan, who turns in perhaps his best performance as the beleaguered Adam Lang, a man who is little more than a pretty face in a nice suit to figurehead the motivations of others. It’s a subtle performance, a man deluded into thinking he has a legacy, slave to the policies set out by his betters. But Brosnan sells his helplessness with incredible charisma and empathy. When he arrives on scene, you want to believe he is what he claims to be, despite all evidence to the contrary.

It’s a film that’s slow to unwind, but when it does get to its tension points it does so with an understated brutality that feels all the more real for doing so. In many ways I was reminded of Michael Clayton, another thriller with a similarly muted sense of tension. And like Michael Clayton, it lives by its inspired cast. Also like Michael Clayton, it’s a fantastic film.

The American

directed by Anton Corbijn

The American is a quiet, understated film, a modern spin on French new wave cinema. As such, for a film about assassins and for the brutally violent opening, most of the run time of The American is muted and incredibly understated. Clooney’s unnamed assassin finds himself in a beautiful Italian village building a custom rifle for another assassin. At the same time, forces seem to be gathering against him, enemies hidden around every turn.

It’s a film content to be still, about the paranoia of a quiet morning spent contemplating the obvious oncoming fate, the presence of an actor inhabiting a role so comfortably that there’s little need for exposition or even dialogue. Instead it is devoted to a unique visual beauty—a fog drenched Italian city, beautiful women lit dimly in questionable places, the stark grace of Clooney assembling his instruments of death. The American is the most European of movies on this list, with sensibilities that run counter to most of modern cinema.

Which is what makes it so compelling to watch. The movie is intense and remote, an internal monologue that the audience is never let in on, relationships that are hinted at but rarely explored, and all driven by Clooney as a man of deep emotion and few words trying to keep alive and morally intact. It is a movie wrapped around the gravity of a single performance, that of Clooney reaffirming the argument that he’s the biggest star of his generation.

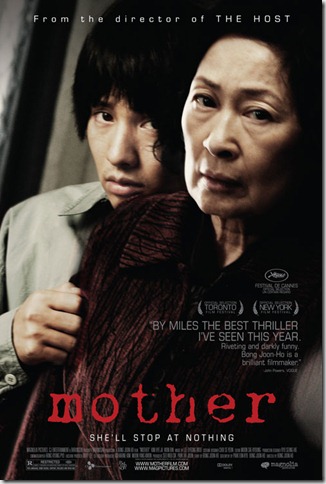

Mother

directed by Bong Joon-ho

This all comes crashing down when a high school girl turns up dead and circumstantial evidence places Do-joon near the scene of the crime. The police, incompetent and bowing to intense public pressure (see Lady Vengeance for another example of appalling South Korean police work, which makes me wonder if there isn’t some truth to it) railroad Do-joon into custody, slapping him with an ineffectual attorney and tricking him into signing a confession.

This begins a quest by the Mother to prove Do-joon’s innocence, a trek that takes her throughout the town, uncovering the seedy truths of the world around her, finding her working with people she previously despised, as the truth slowly begins to reveal itself to her.

The trappings are straight out of the best noir, but where Mother excels is in how quickly it transcends them. What begins as one story slowly morphs into another, as events take wild left turns that shock and horrify, but never seem out of place. It is an amazing character study, a deep exploration of just how far a parent’s love can go, and the dark places to which it leads. It is in many ways a genre mashup, a close-to-the-vest thriller, a strangely touching character piece, all wrapped in an amateur detective story. But it remains incredibly compelling, powerfully acted and beautifully shot, even as it strays down the darkest of alleys.

I’m Still Here

directed by Casey Affleck

I’m Still Here is first and foremost an uncomfortable film. Even knowing that Joaquin’s performance as an unraveling version of himself is indeed a performance, it’s painful to watch. He’s erratic, moody, his body and thoughts seeming to disintegrate in tandem from the figure audiences had come to know from his movies. That it’s captured with all the graceless mess of a seemingly home movie makes it all the more jarring. It is a party that has long since ceased to be fun, yet everyone is still there going at it just the same.

It’s obvious even from the beginning that his aspirations at a music career are little more than a pipe dream. He’s actively terrible, clueless as to how to begin and pushy and oblivious when people start trying to call him on the fact that he’s no musician. Yet, for all of this, the people closest to him and the people fartherst away, the celebrity watchers, do nothing. And that’s where the most troubling aspects of the movie come in. Despite his obviously unwell state, nobody stops it. Nobody from the outside steps in and tries to intervene. The celebrity gossip machine marches forth, jokes aplenty, steamrolling over what could have been the last gasp of a very troubled man. But who cares, right? Everyone is far too self-invested or too skeptical to genuinely be concerned.

It’s a good thing the performance was just that, because otherwise everyone on that film would have been an accomplice to something awful, obviously neglecting a person in need of serious help. And it’s that neglect that is most obvious in the film. This idea of stardom, of expectation, comes with it an easy disregard when people don’t live up to those images we project of them. Joaquin puts himself forward as a sacrifice to this machine of parody and spite, turning the lens more on it than himself. It is not a perfect film, but it’s a movie that dares to turn our fascination with celebrity back on us and ask whether or not we truly care or are just looking for the next scandal, the next tabloid explosion.

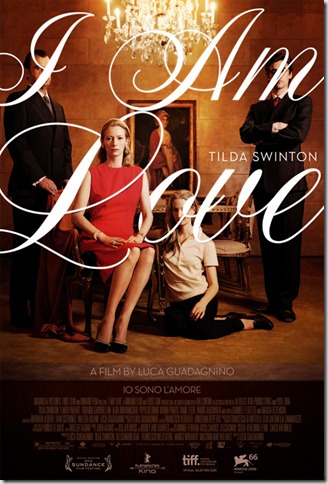

I Am Love

directed by Luca Guadagnino

I Am Love is a movie about the wealthy Recchi family, Italian textile manufacturers. Tancredi, recent heir to the family business, is left in co-ownership with his recalcitrant son Edoardo. Tancredi’s wife, Emma, played by Swinton, is a native-Russian who in this period of familial turmoil begins to grow disaffected with the formal matriarchal status that has been thrust upon her, and begins to explore the idea of an affair with her son’s best friend, a chef named Antonio.

Which doesn’t begin to touch the magic of this movie. The reality of I Am Love is one of a passionate spirit, long fettered by responsibility, beginning to shake that repression and rediscover a more sensual side of life. And it is expressed to perfection by the etherial Swinton, who carries the entire film, selling the fact she speaks Italian and Russian and not a lick of English, incredibly empathetic as a woman who is exploring new frontiers in her life.

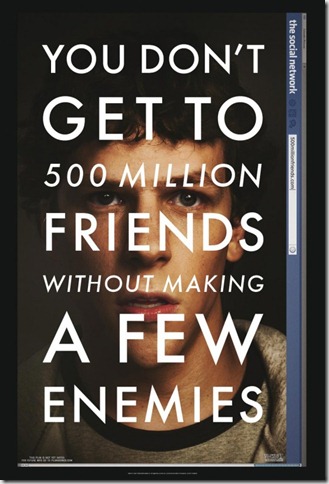

The Social Network

directed by David Fincher

Love him or hate him, Zuckerberg is a presence in the world. But Fincher and Sorkin’s triumph is dragging what is a very insular, introverted personality out onto the screen, to be analyzed and critiqued and finally made relatable. For all the buzz about how negative the portrayal of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg is in this movie, Jessie Eisenberg’s portrayal is, from the first moment, of a fragile man uncomfortable with everything in life but the inside of his own head.

It’s easy to melt down the film into the broad strokes of what did or didn’t happen, but what’s great about The Social Network is how little that reality matters. The movie isn’t about telling us a true story, it’s about showing the perils of genius, the tenuousness of friendship in the face of ambition, and the ephemeral nature of all of our relationships in the modern era. Enemies, rivals, friends, business partners, it’s all relative and fluid and changing at the speed of light. The Social Network is a frame of interaction in the era of the internet, both seen from the outside and living in that moment. It is the first great comment of many on the aughts, reflective without nostalgia, critical without anger or ignorance.

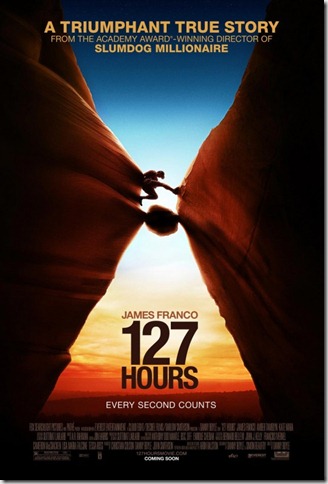

127 Hours

directed by Danny Boyle

Except that’s not really what 127 Hours is about. Yes, Franco as Ralston gets trapped under a rock. And yes, it has a similarly gruesomely triumphant ending, but the reality of the film is vastly different than the abstraction.

First off is Danny Boyle’s typically hyperkinetic style. It creates an amazing juxtaposition here between the modern life and internal monologue of Ralston and the incredible, monolithic static position he finds himself in. It’s a film that balances perfectly between the concrete and the subjective. It’s a delicate line, but it is expressed with incredible compassion for the subject matter.

But the real key is the story that’s hung upon the facts of the situation. Ralston’s story is one of survival, but in Boyle’s hands its transformed into an ode to the human spirit. It is about the need for others, the struggle of the individual versus the social realities of today, a flawed hero discovering truths through suffering that would never have otherwise occurred to him.

It all runs a huge risk of being saccharine and preachy, but the film is neither of those things. It’s swift and beautiful and shocking, but never does it rely too heavily on sentiment. There isn’t enough lucidity in Ralston’s experience, and too much bravery in Franco’s performance, for anything so easy.

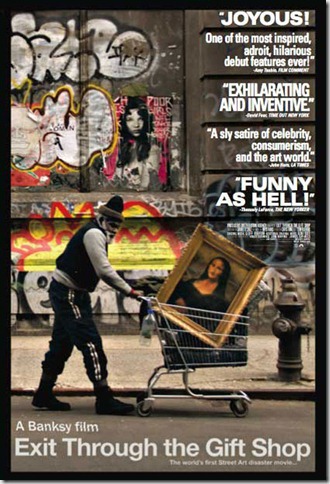

Exit Through the Gift Shop

directed by Banksy

Initially the story of Thierry Guetta, a French immigrant in Los Angeles who becomes obsessed with street art. Taking a camera and heading out into the night, he begins assembling the largest collection of first hand footage of the subject ever assembled, charting much of the emergence of the movement. However, after an encounter with the enigmatic Banksy, it is revealed that for the thousands of hours of footage Guetta has filmed, he has no motivation or ability to put it together into the documentary he’s so fervently talked up. Banksy offers to take custodianship of the footage in order to piece together something coherent from the madness and sends Guetta off to practice the street art he’s been so fascinated with.

What happens next is part farce and part scathing critique of the art community, but it never feels untrue and never descends to outright parody. Exit Through the Gift Shop is amazing in how fine a line it walks, exploring the pretentions of the art world without openly criticizing them or where they come from, encouraging people to explore their own artistic talents by interviews with the most passionate, devoted street artists of the medium. But it’s also a cautionary tale, a story of too little talent and too much ambition, the power of hype, the dangers of association.

It is the perfect companion piece to a movement as controversial and divisive as modern street art, a loving tribute and a bitter critique, all wrapped up in an otherwise straightforward attempt to chronicle the history of the form. The film is a work of art, Banksy’s insightful commentary on a medium he rose to the top of, a fable about dreams and where they can get you. Truth or not, it is honest and incredibly compelling.

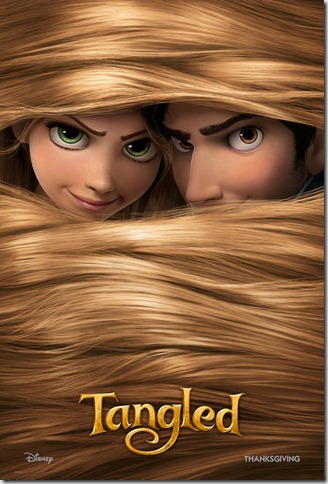

Tangled

directed by Nathan Greno, Byron Howard

Thankfully, the ads were simply terrible, and the movie was not. In fact, it was great. Tangled is easily the best thing Disney’s produced since Lilo & Stitch, and might belong to some of the best of their work from the mid-90s. From the incredibly expressive, painted art style of the CG to the smart updates of the ‘Princess’ mythologies of Disney’s greater works, Tangled is a pretty remarkable achievement from a studio that’s been turning out work that ranged from meh to downright bad for years.

The real triumph of Tangled is in its characters. Rapunzel balances the enthusiasm of a young woman just learning to explore the greater world with the sadness and neurosis of someone who has been so reliant upon their (abusive) caretaker all their life. The male lead, Flynn Rider, is a great subversive send up of the typical bravado-driven male leads in animated features in the past two decades without falling into easy parody.

But the really amazing thing here is how the villain Mother Gothel, the woman who kidnapped and raised Rapunzel for her magical hair, relates to Rapunzel. It’s an amazingly subtle dynamic, a parent who keeps her child under her thumb by instilling self-doubt and poor self-image through infuriating and all-too-relatable passive-aggressive jabs. It’s a smart piece of work, and speaks to a more realistic way people relate to people, and parents sometimes relate to children, than you see in almost any animated feature that isn’t by Miyazaki.

It’s a surprising movie, on all fronts. There’s a maturity of story-telling, without relying on pop culture references or jokes that only play to adults or kids, that is hard to resist. There was a time when Disney produced some of the greatest movies, not just of animation but of the medium of film. Tangled is a great attempt to once again reach towards something greater than the narrow, disappointing box most children’s animation has been in in the modern era.

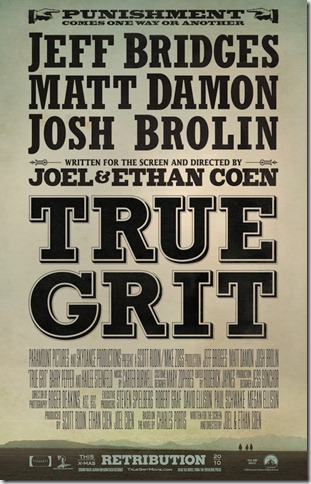

True Grit

directed by Joel and Ethan Coen

True Grit is, at its core, a coming of age story. One girl with one task, set out in a world of uncertainty and danger, trying to find her way. Which seems almost too simple, but in the Coen Brothers hands becomes something pretty magical. What purports to be a morality tale about the triumph of good over evil becomes an awakening to the villain in all people, the goodness and honor that even murderers carry. From the first scene, where young Mattie Ross stands stoically as condemned men speak their last words before being hanged, to the end where she is negotiating with outlaws, it is a morality tale set in an amoral time, a piece that makes no moral judgments. The men Mattie hires are as good and as evil as the man she seeks to capture.

It’s amazing that a film hinges so heavily on an unknown actress, but Hailee Steinfield stands up to Jeff Bridges and Matt Damon giving pitch-perfect performances and not only holds her own but steals many of the scenes she’s in. Special mention needs to be given to Damon, however, who is at his unlikable best as a boastful, slimy Texas Ranger who hits all the right notes of being an utter ass but who is, in many ways, the only real hero of the story. It’s an impressive, surprising piece of character work, up there with Damon’s perfect performance in The Informant.

For all of its intimacy, though, True Grit plays out with the epic scope befitting a Western. The Coen Brothers shoot a beautiful film, a dirty revisionist take on the Western that sometimes ascends to the abstract without feeling jarring. It is the desolate landscape writ large, made immediate and evocative, the perfect existential setting for the characters to inhabit. And they take to it perfectly, with some of the best dialogue in any movie this year, and one of the most compelling small character pieces. For all the buzz Winter’s Bone got this year, I feel this is the movie that best reflects a young woman navigating through a space where the world of black and white becomes a world of greys.

Black Swan

directed by Darren Aronofsky

Yet for all of the precarious wire-work the film does in moments like these, when the erotic thriller moments dictate the plot beats, Black Swan is a film to be marveled at. Because as dangerously close to camp as Black Swan veers, it does so within the context of its story, one of madness and unreality, the artifice of art and the all too real impacts it has upon those who pursue illusive ideas like ‘perfection’. Black Swan is a movie almost beguilingly without a twist, the ending presented to you within the first ten minutes of the movie yet so perfectly pitched that even when you know how it will (how it must) end, you find yourself wishing for a different result.

And that is the genius of the film. As Natalie Portman’s character Nina descends deeper and deeper down into a place of devotion to craft that we know will exact a high price, we are torn between wishing it didn’t have to be this way and breathlessly hoping to see what emerges once she passes that metaphorical line in the sand. And Portman doesn’t disappoint. Her performance is the best she’s ever done, easily the best acting I have seen this year (and many others), until the finale, when the curtain falls and we’re left with an inevitable end that still manages to touch and move with an immediacy and passion that belies its ancient roots.

Black Swan is more than a great movie, it is also a great dark fairy tale, a mood piece on art and personality, about the warring sides within all of us, and about the eternal chase for the impossibility of perfection and the power of humanity to realize artistic dreams at any cost.